Photography and the Importance of a Proper Training

In photography, among the various activities falling under the ‘preparation’ label, training is oftend underevaluated. Just as many newcomers to the world of guns think that buying expensive equipment will make them better shooters, many photographers think that mastering a bunch of exoteric camera settings will be enough to get decent pictures. This is summed up in a common piece of advice to novice shooters (of both guns and cameras): get out there and shoot. Results will just happen.

I have nothing against a ‘Zen’ approach to things, based on instinct and intuition, but my Western, Benthamite mind does not allow me to forget that preparation is necessary to achieve a decent result. In this regard, the British Army’s 7Ps rule is a fundamental piece of advice that does not just work on the battlefield. It should be a mindset to develop, if not for life in general, then certainly for photography. In the domain of visual art, the importance of careful preparation is beautifully explained by Bruno Munari, a giant of industrial design, in his book ‘Da cosa nasce cosa’ (literally ‘From what comes what’, but actually a play on the word ‘cosa’, which in Italian means both ‘what’ and ‘thing’).

Fair enough, one may say, but where does all this muttering lead? This simple question requires an articulate answer based on the idea that in photography the eye should be equally (if not better) trained than the camera handling skills.

At the beginning of my career, coming back from a gig I used to look only for the good pictures, just forgetting of the bad ones which I labeled as just ‘unfortunate’ or ‘missed’. I blamed the AF, the lens, the sensor… you name it. Whatever but the main responsible for having taken a poor picture: the man behind the viewfinder. So I started paying more and more attention to what I was doing wrong and trying to correct mistakes with specific exercises.

Let’s get to some examples.

In this picture, taken with a Leica M9 and a Summicron, I simply did not get the focus right.

You might wonder what the point of using a manual focus lens (and camera) to capture a highly dynamic event such as an MMA fight is, but that is not the point. In fact, I took this next picture with a Canon 5D Mark II and a Canon EF100-400 and the result was the same.

Shooting from behind a cage or fence is not unique to MMA events. Discus and hammer throwing events in athletics, for example, present the same challenges as the photographer is not allowed to be in positions where he could be hit. In this case, manual focus works better than AF (which explains why the M9 was an acceptable choice for the cage fight). You just need to learn how to focus properly (and quickly enough) to focus on the athletes and not the fence. It is also important to learn how to remove the fence completely from the composition. With a prime, this means that the lens should be touching the fence, while a zoom allows more leeway. However, it is not easy to choose the right point of entry.

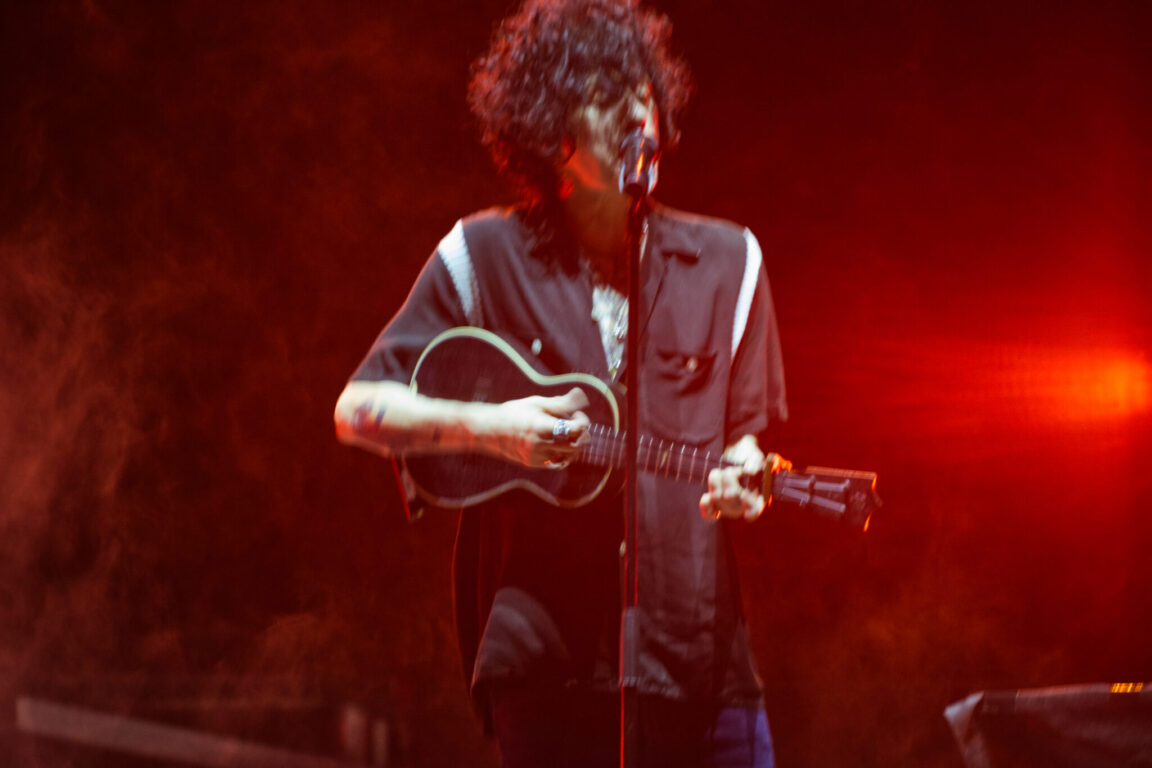

The next image is another example of how important it is to be able to adapt to changing conditions in real time, which is the norm at live events where fog as well as light is present.

I was trying to capture the intense expression on LP’s face, but the sudden combination of light and artificial fog just made the AF go haywire.

Being capable of recognising a correct composition is also what tells a good (or decent) photo from a bad one.

In this picture, taken at an Al Di Meola concert, I did not realise that I was missing the bandoneonist’s feet: a few minutes of angle ruined the shot.

Speaking of composition, this next photo of jazz bassist Jeff Berlin getting ready for a gig explains the difference between a photography and a casual shot.

Not only it is out of focus, but it is also just meaningless. It does not capture the interaction of the musicians, the point of view is wrong, and the excessive space behind Jeff Berlin cuts off Gabriela Sinagra from the other side.

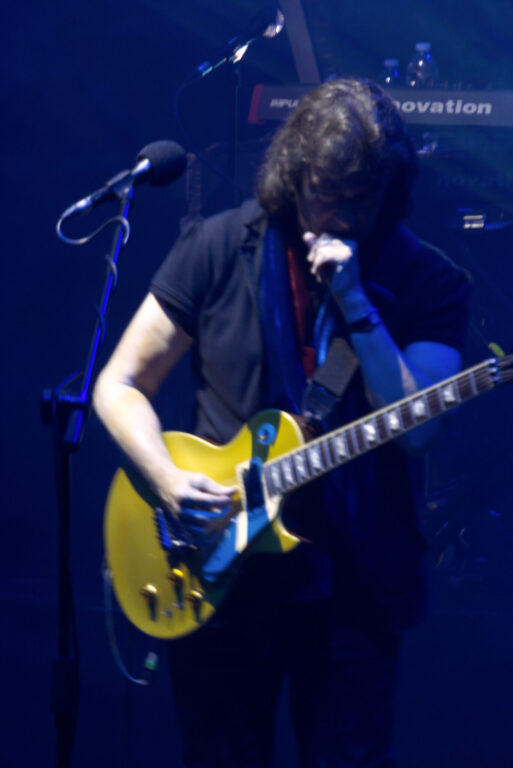

Here I made the same mistake: too much space on one side of the image cut off Steve Hackett’s Les Paul headstock. I also failed to take into account the sharpness problems caused by the presence of an extender.

In short, to paraphrase an old saying, (at least in event photography) you never get a second chance to make a better picture.

This leads to the conclusion of the article: firstly, cameras and lenses should not be blamed for missed or bad photos, as I have made mistakes with a wide range of pieces of equipment. Secondly, I regard bad shots as a treasure, because they expose my own weaknesses and give me guidance on how to overcome them. So I spend more and more time analysing what went wrong, designing training exercises to fix the problem and practising the exercises in non-working moments.

It is a boring activity, sure, but it pays dividends when ‘the moment’ comes.

P.S. Not all my photos are that bad. Sometimes I also get some lucky shot.

Initially published on 35mmc.com.