Legal Apartheid

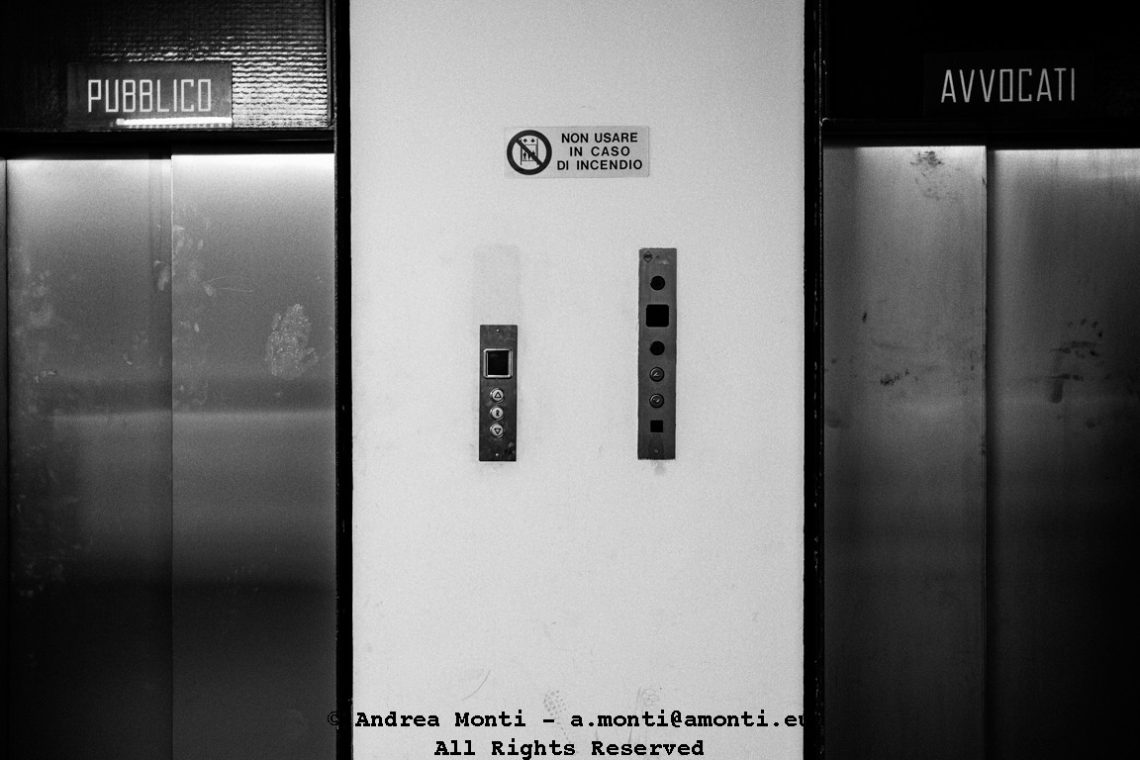

Two elevators, side by side, divided not by function but by status. On the left, a small sign reads Pubblico. On the right, Avvocati. Between them, a strip of blank wall holds the call buttons and a standard notice: Non usare in caso di incendio. The symmetry is perfect, the contrast sharper for it.

In the Court of Rome, this arrangement makes practical sense. Lawyers must move quickly between hearings; delays can derail the fragile timetable of justice. Efficiency demands a separate lift. And yet, looking at it here—reduced to a flat, black-and-white composition—the logic fades, and something else emerges.

The brushed steel doors are marked with smudges and fingerprints, traces of the many hands that have passed through. The public elevator’s panel is intact. The lawyers’ side shows gaps where buttons or plates have been removed, as if even its mechanics are kept apart. The space between the lifts is only a metre wide, but in that metre lies the suggestion of a hierarchy: those who plead, and those who wait to be heard.

Photographed like this, stripped of the noise of the courthouse, the image becomes less about transport and more about access. About how architecture quietly encodes privilege. You could ride either lift, but the signs above make sure you know which one was meant for you. Legal apartheid, rendered in stainless steel and silence.