Histoire d’O

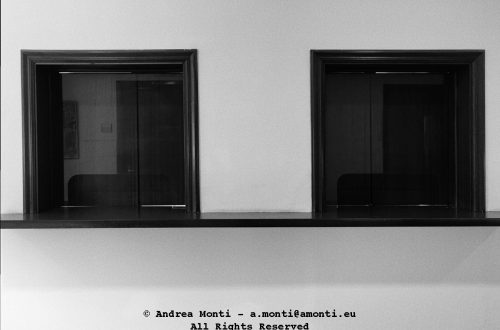

Photography has a curious relationship with meaning. Sometimes it offers us a direct line to an obvious narrative; other times, it teases us with ambiguity, compelling the mind to reach for significance where perhaps none exists. This image—an aged, weathered architectural oval, framed in peeling plaster—belongs firmly in the latter category. Its title, Histoire d’O, borrows knowingly from the controversial novel of the same name, inviting the viewer to read into its form, its texture, and its emptiness.

Technically, the photograph demonstrates a strong command of tonal control. The black-and-white treatment emphasises the interplay between texture and shadow, revealing the rough grain of the plaster, the fine cracks tracing across the surface, and the gentle fall-off of light in the concave centre. The decision to shoot front-on ensures symmetry, giving the oval an almost iconic presence, while the cracks and imperfections provide the counterpoint—order disrupted by time.

Compositionally, it is spare but deliberate. The oval occupies a dominant position, framed tightly to eliminate distractions, allowing the viewer’s attention to rest fully on its shape and surface. The straight-on alignment communicates a formal, almost reverential approach, which works well in the context of the title’s playful nod to literary provocation.

Exposure is well-balanced, maintaining detail in both the lighter stucco and the darker recesses. There’s enough shadow depth to create dimensionality without losing any of the subtle midtone variations that give the texture its tactility. Focus is precise, sharp from edge to edge, allowing the viewer to appreciate the fine degradation of the surface.

What elevates the image beyond a straightforward architectural study is precisely this interplay between form and interpretation. The human mind, ever hungry for narrative, seeks to map meaning onto the “O,” reading it as symbol, metaphor, or even portal. Whether the photographer intended this ambiguity or simply captured an intriguing shape is beside the point—the image works because it allows the viewer to step into that space between recognition and invention.

In short, Histoire d’O is a reminder that photography’s greatest power may be less in telling stories and more in prompting us to imagine them.